From Alberta's First Natural Gas Discovery,

a booklet published in 1981 by PanCanadian |

This is a story about Alberta's first natural gas discovery and the fun

I had finding it. It was my very favorite project of all the things I

did during the 24 years I worked at PanCanadian Petroleum (now EnCana

Corporation).

This presentation debuted at the Petroleum History Society Luncheon on

September 20, 1995 and was repeated at Inter-Can - The Calgary Oil

& Gas Show on June 19, 1997.

An anniversary gift for the CPR

Robert W. Campbell initiated this project in 1977. He was Chairman and

CEO of PanCanadian, which was 81% owned by Canadian Pacific. The Canadian

Pacific Railway's centennial was coming up in 1981, and Mr. Campbell chose

this project as PanCanadian's way to commemorate 100 years of incorporation

of the CPR.

He asked Bill Webb to find Alberta's first gas well. I worked for Bill

Webb in Exploration Administration, and he brought me in on the project.

Location was common knowledge

It was common knowledge in the industry that the CPR discovered gas in

a water well at Langevin siding in 1883, and drilled a second well in

1884. But the exact location and other details were unknown.

Bill Webb and I visited the discovery site, about 35 miles west of Medicine

Hat, in July 1977. Its legal description, for those who like well locations,

is 03-29-015-10-W4.

The site has had three names. Originally it was Langevin Siding.

In 1910, when settlers were coming in large numbers and a town arose,

it was called Carlstadt. After World War I, around 1915, the name

was changed again to Alderson, its current name (but there isn't

much there anymore).

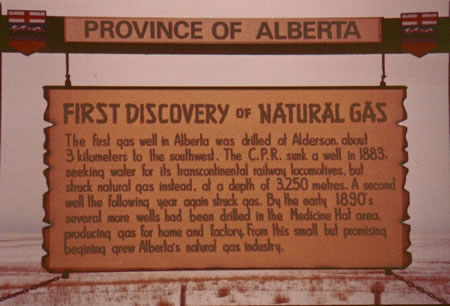

1970s highway commemorative sign

This highway point-of-interest sign was erected in the spring of 1971

as a result of an argument between Mr. Justice A. J. Cullen and Mr. R.

L. Jardine. Rolly Jardine, a court reporter at Lethbridge, told me that

he and Justice Cullen both claimed Alberta's first gas discovery was made

at their home town. Justice Cullen was from Bow Island, and Rolly Jardine

was from Alderson. As you can see, Mr. Jardine won.

The sign reads:

Province of Alberta - First Discovery of Natural Gas

The first gas well in Alberta was drilled at Alderson, about three

kilometres to the southwest. The C.P.R. sunk a well in 1883 seeking

water for its transcontinental railway locomotives, but struck natural

gas instead, at a depth of 3250 metres. A second well, the following

year, again struck gas. By the early 1890s several more wells had been

drilled in the Medicine Hat area, producing gas for home and factory.

From this small but promising beginning grew Alberta's natural gas industry.

Notice anything odd on this sign?

Canada was changing to metric in the late 1970s, and this sign had been

"metricated." Only they goofed. According to the sign, this

old well found gas at 3250 metres, or over 10 000 feet! That depth was

probably impossible with a cable-tool water-drilling rig. The correct

depth is 325 metres or 1155 feet.

Research at The Calgary Herald

Mining and Range Advocate and General Advertiser

These old wells left quite a foot print. There is quite a bit of evidence,

especially considering that this was really the wild frontier in 1883.

I will show you the actual written records to let the past speak for itself.

One of the first places I went to do research was the Herald, which was

conveniently located in their old downtown building. I read microfilmed

issues of The Calgary Herald Mining and Range Advocate and General

Advertiser from 1883 to 1885. This made me feel woozy as the microfilm

scrolled up as you moved through the papers. Luckily they yielded some

valuable information.

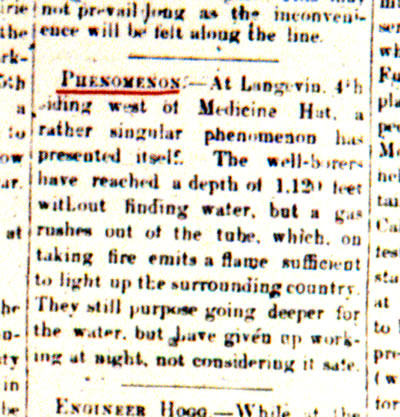

On December 12, 1883, they reported:

"PHENOMENON. - At Langevin, 4th siding west of Medicine Hat, a

rather singular phenomenon has presented itself. The well-borers have

reached a depth of 1,120 feet without finding water, but a gas which

rushes out of the tube, which, on taking fire emits a flame sufficient

to light up the surrounding country. They still purpose going deeper

for the water, but have given up working at night, not considering it

safe."

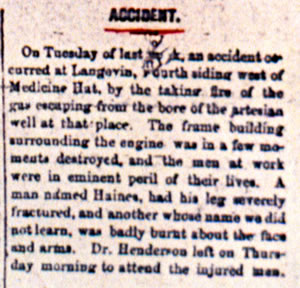

Then in the Herald of January 16, 1884 (note date in left image):

"ACCIDENT. - On Tuesday of last week, an accident occurred at

Langevin, fourth siding west of Medicine Hat, by the taking fire of

the gas escaping from the bore of the artesian well at that place. The

frame building surrounding the engine was in a few moments destroyed,

and the men at work were in eminent peril of their lives. A man named

Haines, had his leg severely fractured, and another whose name we did

not learn, was badly burnt about the face and arms. Dr. Henderson left

on Thursday morning to attend the injured men."

I've been told by several historians that historical research often can

be very strange - like you find information when you stop looking and

move on to another subject. These newspaper clippings are a perfect example.

I later discovered that the Glenbow Archives had a microfilm reader-printer,

so I went to get copies of these articles. Strangely these two editions

of the Herald, were missing from the Glenbow's reels! If I had done the

newspaper research at the Glenbow, instead of the Herald, I would have

never have found these articles.

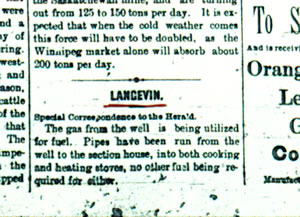

The last reference I found was in the Herald of October 29, 1884:

"LANGEVIN. - The gas from the well is being utilized for fuel.

Pipes have been run from the well to the section house, into both cooking

and heating stoves, no other fuel being required for either."

Research at Canadian Pacific's Archives

Next, I headed to Canadian Pacific's Archives in Montreal. They were in

Windsor Station, which looks a bit like a castle, and the Archives were

in this little turret at the top. (I'm not sure if they are still there,

as the station was renovated. Update January 2007: They are no longer in the turret, but on the ground floor of the station.) The Archives was furnished with wonderful

old furniture, which added to the exciting historical atmosphere. Here's

a fine old roll-top desk and bookcase with leaded-glass doors.

I worked at this desk, which they told me belonged to Cornelius Van

Horne, with a bust of the man himself supervising me from the desk corner.

CP Archives are private. When the public - even distinguished authors

like Pierre Burton - wants to do research there, they request subjects

which are found and brought to the Archives for the researcher.

I got the keys to the vault! (It paid to be part of the corporate family.)

The vault was in the basement, and at the time they only had the senior

executives' papers catalogued.

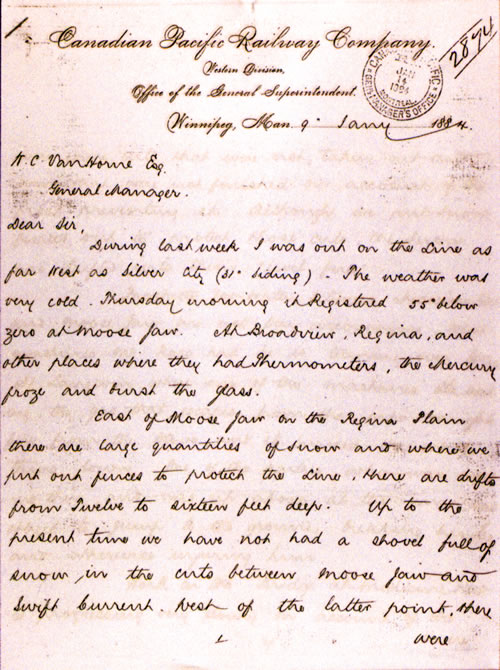

Luckily, I found a memo dated January 9, 1884, from J. M. Egan, General

Superintendent of the Western Division to W.C. Van Horne Esquire, General

Manager. It's some sort of regular report and only a bit of it is about

our well. But I've transcribed the whole thing, which is very interesting.

"Dear Sir,

During last week I was out on the line as far west as Silver City (31st

siding). The weather was very cold. Thursday morning it registered 55o

below zero at Moose Jaw. At Broadview, Regina, and other places where

they had thermometers, the mercury froze and broke the glass.

East of Moose Jaw on the Regina Plain there are large quantities of

snow and where we put out fences to protect the line, there are drifts

from twelve to sixteen feet deep. Up to the present time we have not

had a shovel full of snow in the cuts (?) between Moose Jaw and Swift

Current. West of the latter point, there were some cuts that were not

taken out, and some that were not finished on account of the frost preventing

it. Although we put snow fences out to protect those cuts, the snow

has drifted into them "level full."

(Here we get to our well.) Prospects for water between Medicine

Hat and Moose Jaw are not very encouraging. What machines Mr. Ross had,

he is turning over to us. At Langevin where one of the machines is working,

the gas that escapes from the pipe caught fire from the stove, and it

burned the whole thing down. One of the parties who was working there

and was up above at the time, was obliged to jump to the ground breaking

his leg, and otherwise injuring him.

Work on the Bridge at Medicine Hat is progressing very slowly on account

of the severe cold. The day I was there, all the men were obliged to

quit work, and it was with difficulty that a man could walk across the

River without freezing.

At Calgary there is great excitement, and the boom is making nearly

all the Residents at that point nearly crazy. As I wired you from there,

nearly all the building is being done and lots sold East of the Elbow.

Mr. McTavish says he will have Section 15 on the market this week, and

I suppose that will prevent any further sales in that line. We have

commenced the station there. Have informed Mr. Ross that we would build

same.

There is but little snow at Calgary and it grows lighter until 27th

Siding is reached. There it commences again, and at Silver City there

is about two feet of snow. At the End of Track I was informed that there

was fully five feet. We had twelve cars of freight for Canmore (?) and

Silver City from Calgary.

The Mining craze has started at Silver City, and there are at least

four hundred (400) persons in that neighborhood now. They appear to

be all satisfied with their work so far, and expect to see a large rush

of prospectors in there in the Spring. I was endeavoring, as far as

possible, to have them bring in what tools and provisions they wanted

before Spring opened, as then no doubt we will have trouble on that

Line owing to the depth of snow that is there at present. I went down

in one of the mines. They were then about 100 feet below the surface

of the top of one of the hills about two miles north of Silver City.

They are working in a strata of Limestone between layers of quartzite.

I am in hopes that there will be a rush in there during the coming spring

so that we may be able to realize something by hauling them.

Mr. Ross has had men at work getting out wood and ties.

Yours truly,

James Egan

General Superintendent"

I found this article early in my week's stay at Montreal, but could not

find any other useful leads to the old well. So I used the rest of the

time snooping into other things, like:

- the sinking of the Empress of Ireland - a tragedy worse than the

Titanic,

- the Railway's campaign in Romania to encourage settlers (like my

great grandparents) to come to Saskatchewan,

- Chief Crowfoot for whom my elementary school was named,

- the time the train crashed into the basement at Windsor Station (where

I was currently working),

- old photographs, etc.

It was a wonderful week, and I could hardly believe I was getting paid

for it. Unfortunately, I didn't get to meet the Chief Archivist, Omer Lavallée, who I had talked to on the phone, as he was ill that week.

Research at the Glenbow Archives

Research at the Glenbow Archives also yielded some interesting information.

This little gas discovery had caught the eye of Canada's geological community.

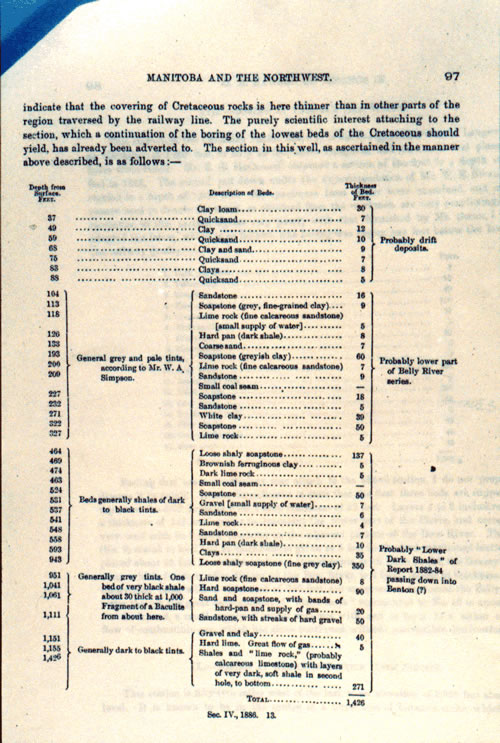

Dr. George M. Dawson of the Geological Survey of Canada, collected information

on the wells at Langevin siding and other wells, and presented a paper

to the Royal Society of Canada on May 26, 1886. The paper was called on

On Certain Borings in Manitoba and the Northwest Territory. I believe

this paper is what kept the Langevin discovery information alive in the

industry.

Dawson provided a great deal of information about the gas discovery,

including a sample description, which you are looking at now. He made

some prophetic comments on the future of oil and gas from such scant information.

Here is some of the section on the wells at Langevin.

"... The wells at this place did not yield any sufficient quantity

of good water, though small flows were met with at several levels. They

have, however, demonstrated the very important fact that a large supply

of natural combustible gas exists in this district, at depths of 900

feet and over, in the sandy layers of the 'Lower Dark shales.' In consequence

of the generally horizontal position and widespread uniformity in the

character of the rocks, it is probable that a similar supply will be

met with over a great area of this part of the Northwest, and that it

may become in the near future a factor of economic importance."

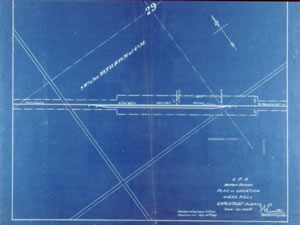

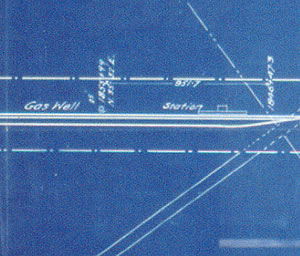

Research at PanCanadian and with Alderson residents

PanCanadian's own files contained this survey plat, dated 1910, which

shows the second well. Eventually I discovered why the CPR Western Division

had done this survey. In 1909, Eugene Coste discovered gas at Bow Island

on what he thought was CPR land. It turned out that it was not CPR land,

so the CPR had to trade other lands with the Crown to get possession of

the discovery land. So, the CPR Law Department ordered surveys and title

searches of every gas well on CPR land.

This was all the contemporary information on the wells that I could find.

But I never stopped searching. I even went to Powell River, BC, where

Dr. Henderson had ended up. I hoped he had left some record of the accident

at the well. I didn't find anything, but a bunch of eager-to-help pensioners

who knew where to get beer during a prolonged beer strike. But that's

another story ...

Bill Webb and I also talked to old-time residents of the area. We never

found out any more information about what happened in 1883-1884. But we

learned about the later years of the second well, the one that was producing.

This photo shows Alderson in the 1920s when the town was thriving.

We learned a lot from Mr. and Mrs. James Warne of Medicine Hat. They

lived at Alderson siding for 10 years from about 1932 to 1942. Mr. Warne

was Section Foreman for this part of the track. In 1932, there were two

section houses and two bunkhouses on the north side of the track, and

the station was on the south side. All these buildings were lit with natural

gas, and they had previously been heated with gas as well. The Warnes

remember that the gas was processed through a separator to remove the

water.

Following a natural gas explosion in 1934 or 1935, the Bridge and Building

Department of the CPR removed all the gas connections to the buildings

and abandoned the well with a few wheelbarrowsful of cement. As far as

is known, this was the first attempt to abandon the producing well after

50 years of production. The Warnes told us the well continued to blow

water for some time after this abandonment attempt. It would form a mountain

of ice by the tracks in the winter. They showed us a photo of their children

playing on this "hill" (the only hill around) with their sled.

To stop the leakage, the Bridge and Building Department added more cement

and rammed a sharpened railroad tie into the casing. Mrs. Warne told us

the well was rumbling and growling one day when the weather was changing.

So Mr. Warne went out to fix it. He smacked the casing hard, which caused

the sharpened railroad tie to shoot out of the well like it was shot out

of a cannon. It went straight up very high, almost into orbit, then straight

back down. Luckily, Mr. Warne was not underneath when the tie returned

to earth. By the time the Warnes left in 1942, the well still leaked gas

but with little pressure.

Between 1942 and 1954, some further attempts were made to seal off the

gas leak with a cement plug placed over the well, probably by the CPR

Bridge and Building Department, but I never found any details. In 1954,

the well was leaking gas quite badly and fissures had formed as far as

20 feet away from the well. The Alberta Oil and Gas Conservation Board

(as the EUB was called then) notified the CPR that the well would have

to be cleaned out to its total depth of 1426 feet and reabandoned.

Reabandonment operations took from July 19 to September 30, 1954 - 2

1/2 months! The abandonment was complicated by odd-sized pipes that modern

tools did not fit, high gas pressures, and much debris in the hole. The

photo shows the well after reabandonment.

Around the time of the reabandonment, references to the discovery well

and the producing well being very close together start to appear. A 1969

book, called Oil in Canada West the Early Years by George de Mille,

told us that the two wells were drilled just eight feet apart. Bill Webb

and I discussed this with John Peake, who was the Petroleum Engineer for

the Department of Natural Resources of the CPR at the time of abandonment.

He said there was no evidence of two wells at the site, and he thought

he only found out about the first well after the reabandonment. I also

talked to Frenchie LeRoux who was the tool push during the reabandonment.

He said he knew there were two wells at the site, but could not detect

the presence of the other. I could NOT find any information to support

the statement that the wells were very close together.

We had learned a lot, but we had not found Alberta's first gas well,

as Mr. Campbell asked. We knew now that we couldn't find it with more

research.

Physical Investigation - geophysics and geology

PanCanadian's Chief Geophysicist, Easton Wren, heard of our plight and

had an idea. He suggested high resolution resistivity, a shallow geophysical

technique, used in civil engineering for bridge or building construction.

It had been used in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt to locate tombs.

It was expected to pinpoint near-surface anomalies in the electromagnetic

response of the soil, such as the disturbance that would have been caused

by drilling.

In this photo, a crew from R. M. Hardy and Associates is preparing to

run the high resolution resistivity survey around the visible second well

on March 15, 1978. The fellow in the middle is Paul Gibson, PanCanadian's

Geophysical Field Supervisor. The long white bar was the tool used.

The survey succeeded in removing most of the station grounds from the

area of probability. Only two anomalies were found, one near the second

visible well, and one in the area where we had been told was the site

of the water separator.

Next, we tried a geological idea. The theory was that the clayish soil

around second well could be contaminated with metals from the casing,

decreasing in concentration with distance. Through a systematic sampling

grid, we could identify another occurrence of the pattern.

This photo shows staff from Chemical and Geological Laboratories. They're

trying to take soil samples near the second well with a rented auger,

in October 1978. The auger kept getting stuck in large, fire-charred wooden

beams. We figured they must be part of the well cellar, or wooden-derrick

debris. The only thing to do now was to dig it up.

Archaeological Dig

In this photo, taken on September 27, 1979, an archaeological crew from

John Brumley and Associates is just beginning the dig. The man in the

maroon jacket near the back of the photo is Bill Webb.

By October 27, 1979, the dig was completed and the well found. Bill Webb

and I visited the dig with the two big bosses from PanCanadian. This photo

shows archaeologist John Brumley in the pit, discussing the well with

Robert Campbell (in the cap), Chairman and CEO, and John Taylor, President

of PanCanadian.

Here it is - the first well to discover natural gas

in Alberta!

It appears that the 1883 discovery well did not leak. Is that possible?

I think so. I believe that the discovery well was abandoned by an experienced

drilling crew. The second well was abandoned by railway crews that really

didn't know what they were doing with a well producing gas and water from

multiple zones.

This photo shows the discovery well and the pits dug by the archeologists.

You can see the fire-charred beams that we kept augering into, and the

debris.

This photo shows the second well in the foreground and the discovery

well in the pit behind. And guess what! The wells are about 8 feet apart.

It took all this work to verify a rumor that popped up 60 years after

the wells were drilled, and then turned out to be TRUE!

When the dig was finished, the archaeologists lined the pits with plastic,

then replaced the soil on top of the plastic. If the area is ever excavated

again, it will be very obvious where the soil remains undisturbed.

John Brumley wrote an article on Alberta's First Natural Gas Wellsite

for the Alberta Archaeological Review, the Spring 1982 issue.

Commemorating the Discovery

Now that the discovery well was found, we proceeded to make a permanent

memorial to commemorate CP's centennial. In September 1980, I wrote a

report applying to Alberta Culture to make the site a Provincial Historic

Resource. The application was accepted. Some time later, Alberta Culture

sent a History Professor to audit me and make sure that our research was

valid. Luckily, I passed.

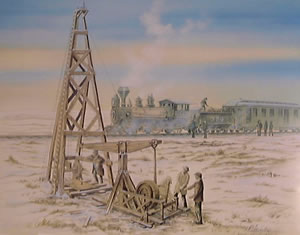

The CP centennial was now close at hand. We had an illustration drawn

of drilling the discovery. I gathered all the information that I could

find to help with the image. Robert Saunders, PanCanadian's annual report

designer, painted the scene. (The original hung on PanCanadian's Executive

floor.) We also used the discovery well as the cover art for PanCanadian's

1980 annual report, which was published in early 1981, the centennial

year. Robert Saunders also designed the booklet that I wrote called Alberta's

First Natural Gas Discovery. There is a copy in the Glenbow Archives.

The next step was to erect a lasting monument at the site - one that

required no maintenance and that was bullet-proof since it would be out

on the bald prairie. Bill Webb researched other sites commemorating discoveries,

many in the States, looking for design ideas. We decided on a cairn, which

was designed by D. S. Bathory, Stevenson, Raines & Partners, who also

designed the interior of the new PanCanadian Plaza building. The cairn

was built by Anglia Steel, and installed by Brooks Oilfield Services in

late 1981.

This photo shows Bill Webb at the site with the installation crew.

Here's the cairn. To keep the public off the railway tracks, the cairn

is set back a safe distance from the wells, and the chain link fence keeps

youngsters from straying onto the tracks.

Here's a close-up of the cairn inscription.

In the early 1980s, Alberta Culture put up a new point-of-interest sign

on the highway using the drawings from PanCanadian's booklet on the wells.

I am really glad that PanCanadian gave me the opportunity to work on

this project, which I thoroughly enjoyed. PanCanadian invested a great

deal of time, effort, and money to find this well. And I'm glad that they

did, preserving the story of these old wells.

I would like to thank PanCanadian for their help with my presentation

today. Special thanks to Bonnie Mech for letting me use the files in PanCanadian's

Archives, and to Ennio Trevisanut for making these photos from a mixed

collection of photos, xeroxes, and copies of microfilm.

Micky Gulless

|